“My name is Kunta Kinte.”

This week I have been watching the remake of Alex Haley’s Roots, airing on the History Channel. It’s brilliant. Watching this updated version has me reflecting back on the original version which I watched as a child. I didn’t realize it back then, but it planted a seed in me which has now blossomed into a full blown passion (some would say obsession) to trace my own family roots back to Africa. The idea that Alex Haley could trace his ancestry back to a noble Mandinka warrior named Kunta Kinte was so powerful to me that it’s inspired me throughout my life to try to do the same.

Roots is also representative of the significant challenges descendants of enslaved people in America face trying to trace their ancestry. Within a year of Roots being published, Haley’s masterpiece faced significant scrutiny. Historians and genealogists uncovered evidentiary flaws in the family history Haley details in his book, calling into question whether the book should be treated more as a work of historical fiction rather than one of historical scholarship.

Ever since I watched Roots, I’ve been on a quest to explore and identify my connection to Africa. The loftiest aspiration I ever let my mind consider was the potential to trace back to a named ancestor in Africa. To identify my family’s Kunta Kinte. My current research leads me to believe that his name could be Emanuell Cambow (Cumbo).

My quest to uncover my African roots started in 1995 when I travelled to Johannesburg South Africa for a year while working for Bain and Company. It had always been my dream to live and travel on the African continent. Within a few days of arriving I struck up a conversation with a South African acquaintance of Zulu ancestry. I asked him, “Hey if I were walking down the street in Johannesburg, what tribe would people think I belonged to?” He chuckled, and then politely responded, “Here in South Africa you would be considered Indian or Cape Coloured.”. I was a bit shocked. I am African American, but I guess I didn’t look particularly African, to him at least.

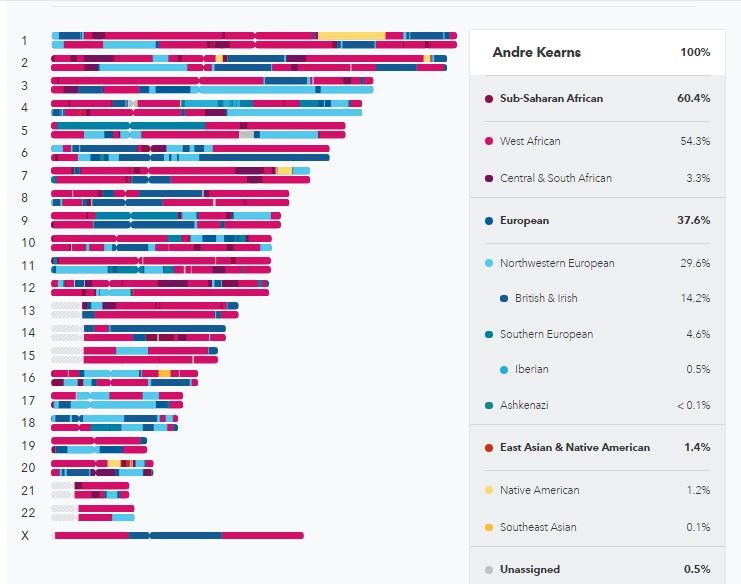

My journey continued with the advent of DNA testing which offers African Americans the intoxicating possibility of leapfrogging research brick walls created by slavery to connect to African roots by analyzing the family history etched within our DNA. There are two flavors of DNA testing currently available – Haplogroup and Autosomal.

Haplogroup is the term scientists use to describe your ancient ancestral clan such as Anglo-Saxon, Ashkenazi Jew or in the case of Kunta Kinte, Mandinka. Haplogroup DNA tests reveal ancient or “deep” genealogical origins i.e. thousands of years ago rather than more recent ancestry. There are two test types – paternal and maternal. The paternal haplogroup test analyzes the DNA markers a father passes down to his son through the Y chromosome to identify ancestral clan. The maternal haplogroug test analyzes the DNA markers a mother passes down to her children through mitochondrial DNA to identify ancestral clan. Autosomal DNA tests examine a person’s 23 pairs of chromosomes to analyze their ethnic makeup.

I started back in 2006 by testing with AfricanAncestry, which is a Haplogroup DNA test service specializing in tracing African ancestral origins. I ended up testing with them twice actually. The first time I gifted my father a paternal haplogroup DNA test. The result came back “undetermined”. Turns out it was because our paternal haplogroup was of European origin (R1b). I later learned that up to 33% of African American men have European paternal haplogroups because of the history in America of white men producing offspring with enslaved women.

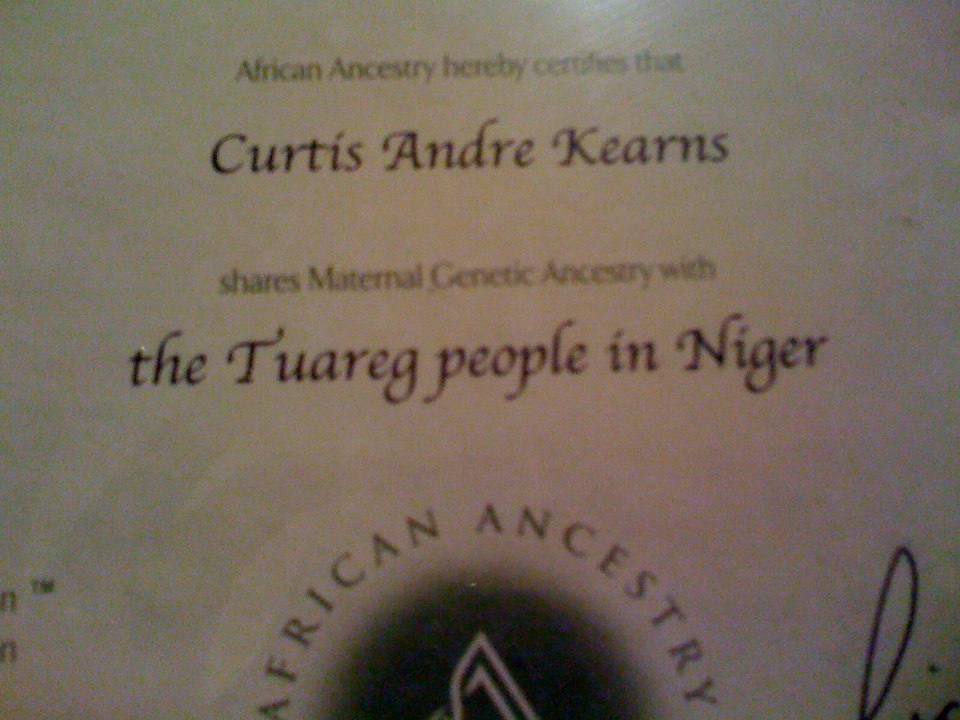

Next I took the AfricanAncestry maternal DNA test. My results came back showing common ancestry with the Tuareg people of Niger. I was euphoric. I’d finally established a true African connection. However I later learned that my maternal Haplogroup was U4, which was of European, Asian or Northern African origin. In a flash, my clear African ancestral connection had blurred into one that could just as easily come from Europe or Asia. It turns out that less than 5% of African Americans possess non-African maternal haplogroups, and I was possibly one of them.

My search continued when I tested a few years later with AncestryDNA which is an autosomal DNA test service. If you are interested in understanding your more recent genetic history i.e. a few hundred years ago and connecting with DNA cousin matches I recommend testing with an autosomal service such as AncestryDNA, 23andMe or Family TreeDNA.

My AncestryDNA test results offered exciting detail on my ethnic admixture (62% African) and the regions from which my African ancestors might have lived – modern day Cameroon, Congo, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin, and Togo. But the results didn’t offer predicted ethnic groups. A neat new service called DNA Land, by the way, now offers the ability to upload your DNA for free and get back admixture results inclusive of African ethnic group estimations.

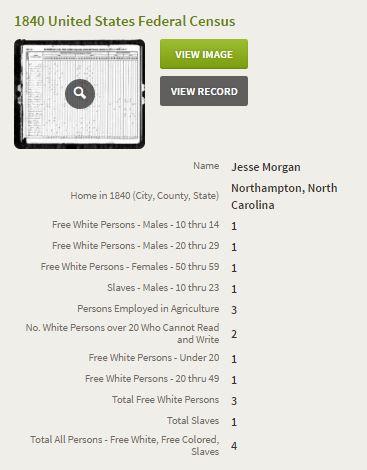

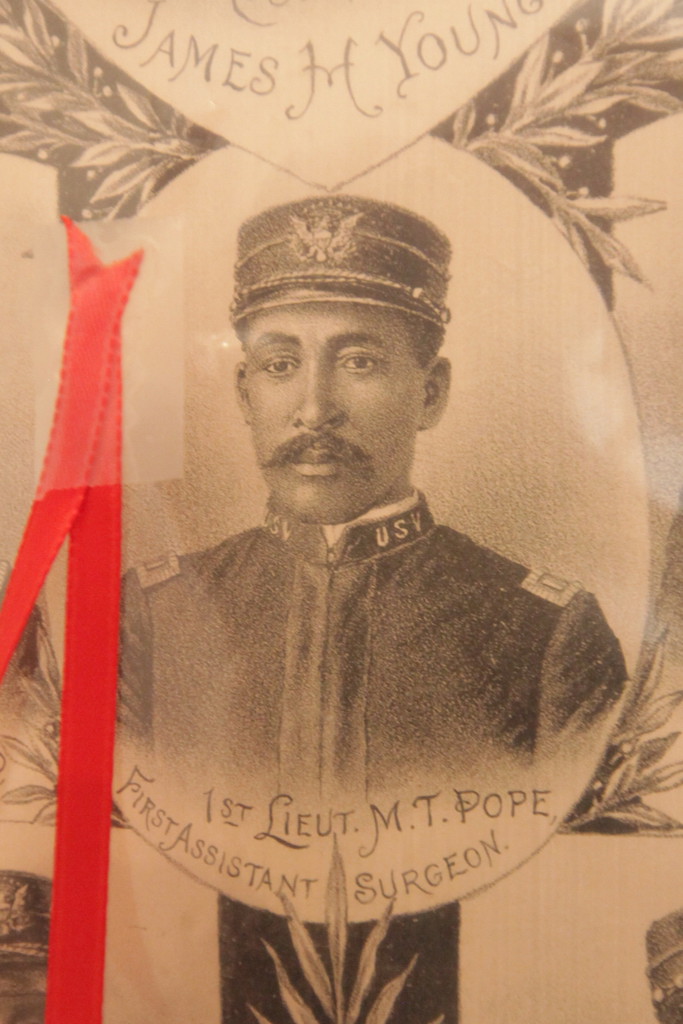

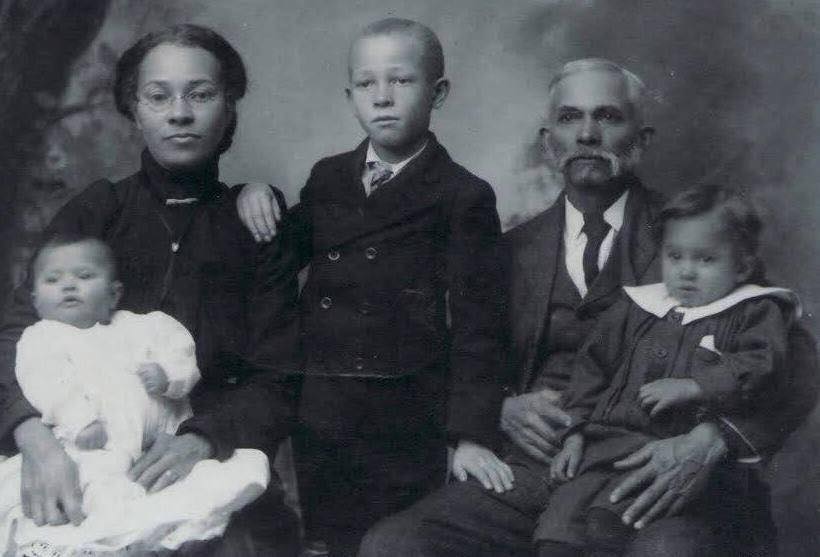

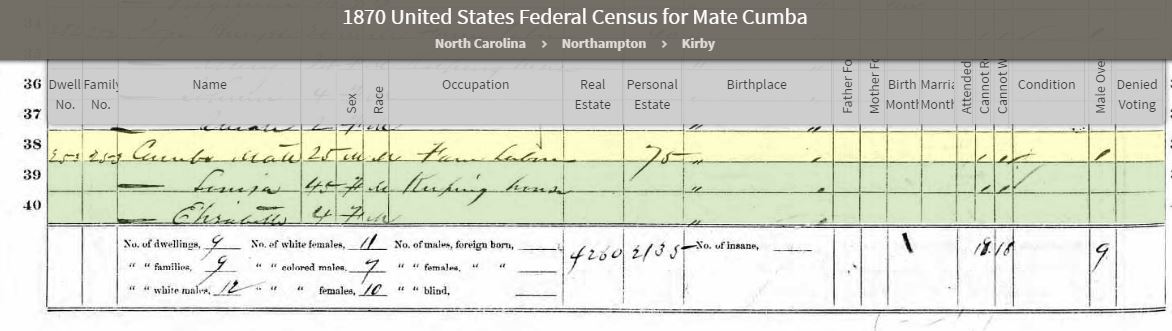

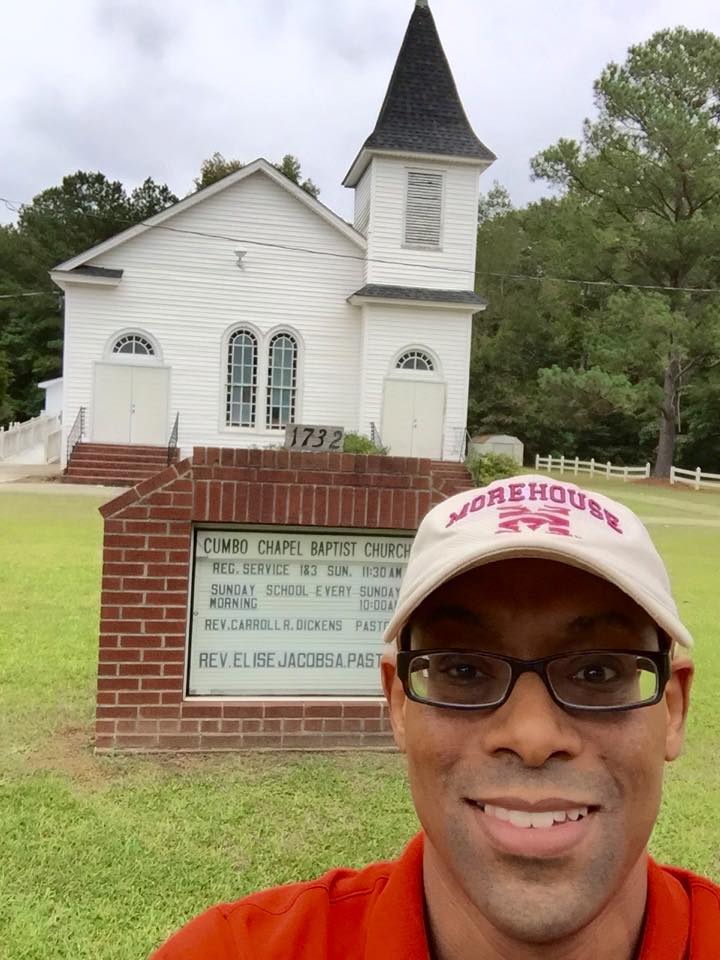

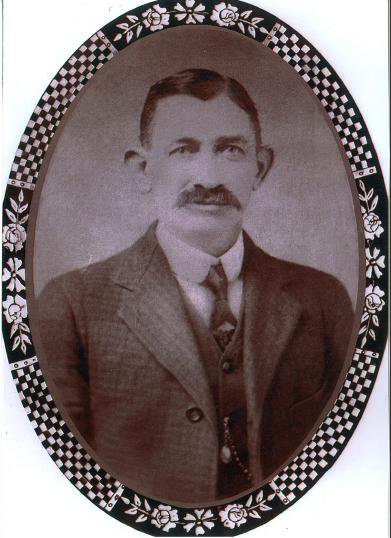

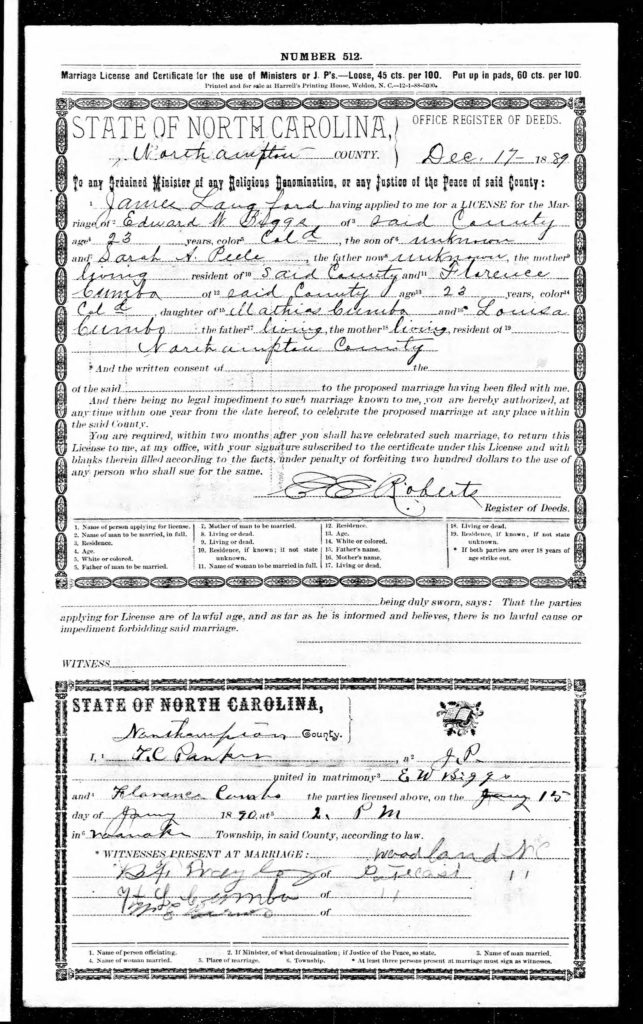

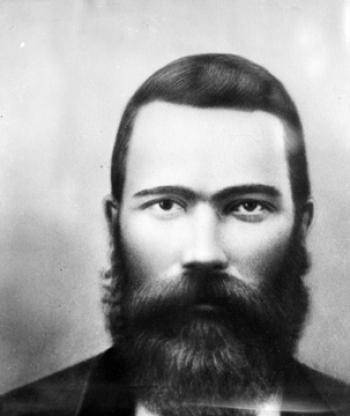

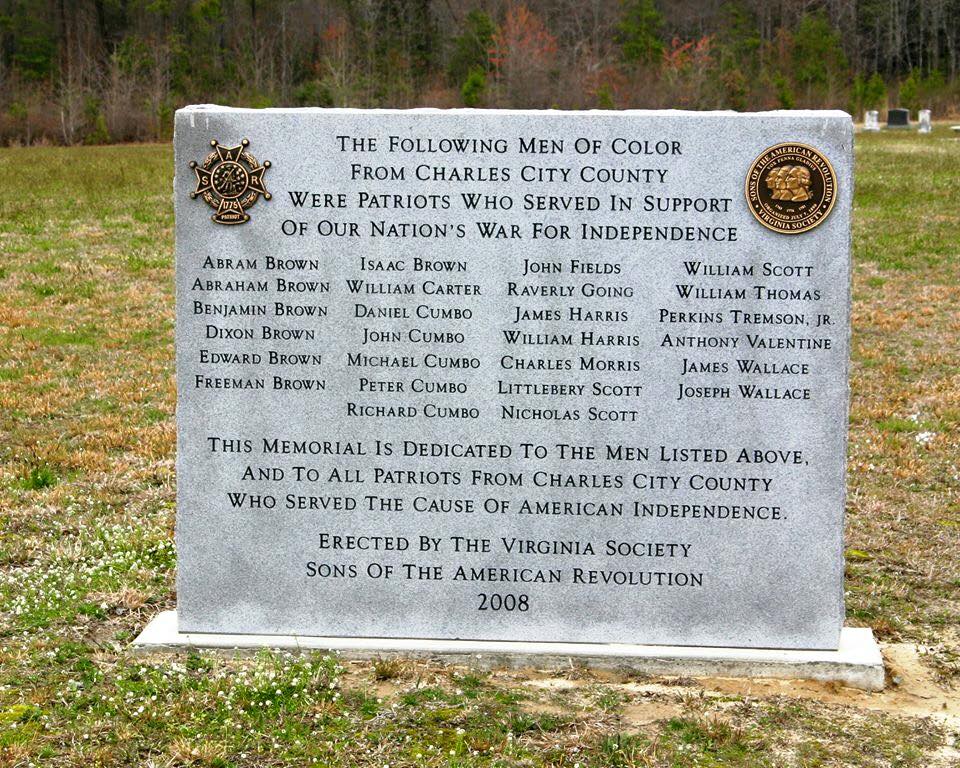

My search now continues through my family tree research. Of my 32 great-great great (3rd) grandparents, I estimate that 21 of them were enslaved, mainly in North Carolina, which for the most part means that my research of their ancestry dead ends in the early 1800s due to lack of documentation. But through research I also discovered that I descend from a number of free people of color including my 3rd great grandfather Junius Matthias Cumbo, son of Britton Cumbo Jr. of Northampton, NC. I discovered that there was more documentation available on these families offering me a slightly better chance to trace these lines much further back.

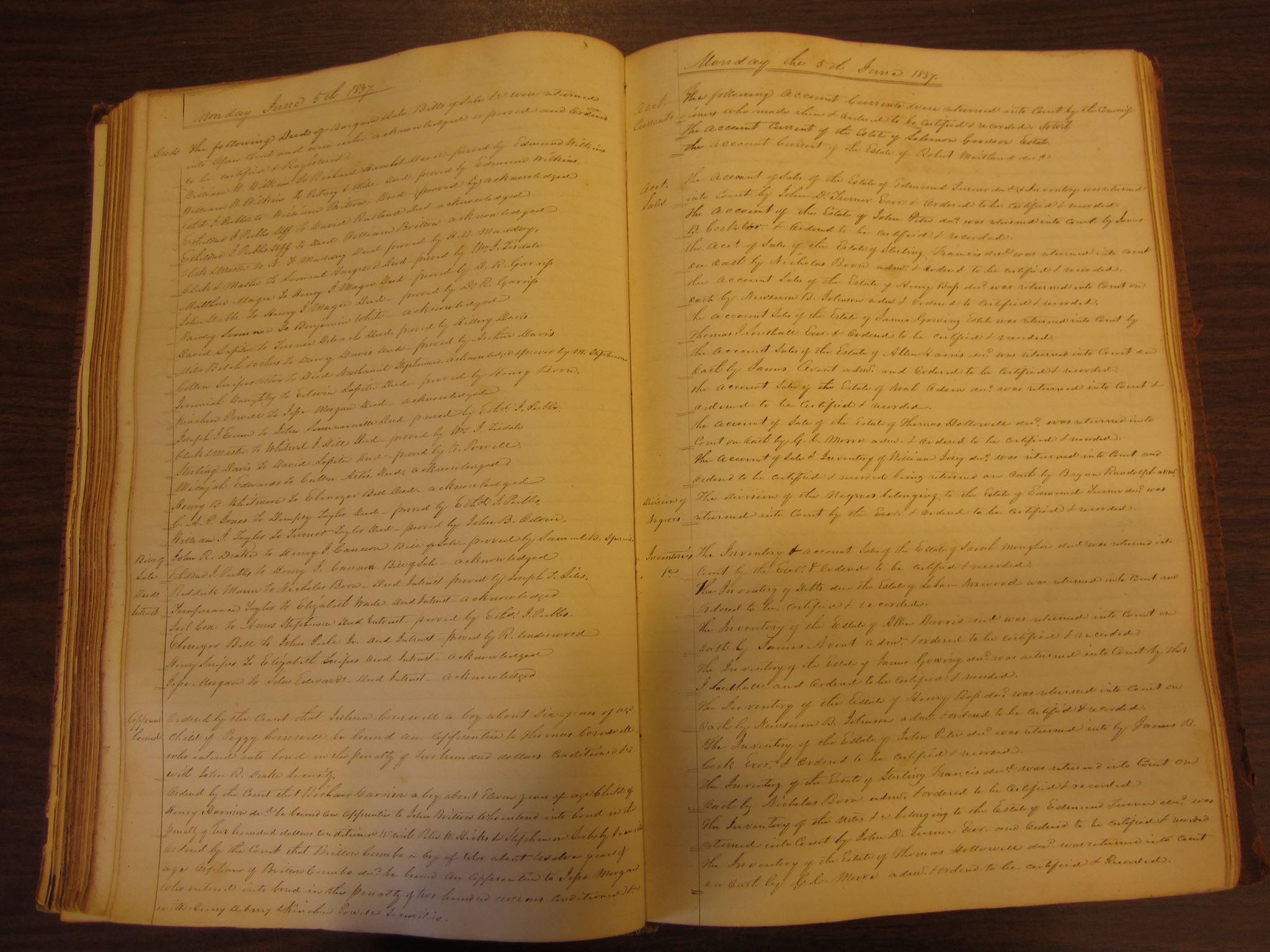

I’ll never forget the day I thought I’d traced all the way back to a named African ancestor. Numerous Ancestry public trees trace Britton Cumbo Jr.’s ancestry back to Emanuell Cambow born in Angola in 1614 and who was patented 50 acres in Jamestown in 1667. When those Ancestry shaky leaves led me back to Emanuell with an Angola birthplace I was once again euphoric. But I’d soon learn that the links from Britton back to Emanuell are not well documented, calling the accuracy of these Ancestry public trees into question. So my current research is focused on extending my Cumbo family tree back another generation or two through validating documentation. It’s painstaking research, like looking for a needle in a haystack. I’m hoping that identifying Britton’s ancestry will take me one step closer toward building a validated lineage connected back to the Kunta Kinte of my family – a man named Emanuell Cambow.

This journey is not easy but with Roots as my inspiration I plan to stay the course.